- Home

- Hammond Innes

The Trojan Horse Page 6

The Trojan Horse Read online

Page 6

‘Well, anyway, he covered what he’d underwritten somehow. He must have needed the better part of four millions, so I don’t imagine he would have been able to find it all himself.’

‘Where would he be likely to get it?’

‘Now look, Andrew, there’s a limit to the questions I can answer. What’s the matter with the fellow? If you’re suspecting him of being a racketeer, I warn you, the whole issuing business is a racket. And the whole City for that matter,’ he added frankly. ‘Or has he got mixed up in a murder case?’

‘He can probably answer that better than I can,’ I said. ‘I’m just curious, that’s all.’

‘Well, old boy, if you take my advice, you’ll pick Home Rails. Try “Berwick” Second Prefs. And have a game of golf with me some time.’

‘I will,’ I said. ‘But just now I’m busy. Many thanks for what you’ve told me.’ And I rang off, wondering whether or not Bernard Mallard knew who Dorman’s backer was.

As I left the club, I saw my friend searching for cigarette ends in the gutter by the R.A.C. I walked leisurely along Pall Mall and jumped a bus as it slowed down to take the corner from the Haymarket. And so to Bush House, where I looked up the shareholders’ list of the Calboyd Diesel Company. Of a total issued share capital of £6,500,000, no less than £4,000,000 odd was being held by three private persons and Ronald Dorman and Company. I put down their names and their holdings. Ronald Dorman and Company had the biggest holding. Then came a Mr John Burston of Woodlands, the Butts, Alfriston. Next, Mr Alfred Cappock, Wendover Hotel, Piccadilly, London, W. And last, Sir James Calboyd, Calboyd House, Stockport, Lancs. Sir James Calboyd was the only big holder who was also a member of the board. Possibly Dorman had nominated a director. That remained to be seen.

I put the paper in my pocket and took a taxi back to David’s studio. ‘Now what the devil have you been up to?’ he demanded, as I entered the room. ‘I was just on the point of sending out a search party.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, and told him what I had been doing.

‘You’re certain you were followed?’ he asked.

‘Absolutely,’ I said.

‘Good! Now we know quite definitely where we are. But what’s the point of taking the original typescript of your statement down to your club whilst, at the same time, you send the carbon to your bank?’

‘They followed me to the club,’ I explained. ‘I think they’ll guess that the first thing I should do would be either to get in touch with the police or to leave a statement for them in case of accidents. My belief is that they’ll burgle the club and, when they find they’ve got hold of the typescript, they’ll not worry so much about the possibility of a duplicate.’

He nodded. ‘My respect for my elderly relative grows hourly,’ he said. ‘In the meantime, I haven’t been idle. Whilst waiting for friend Harrison to return from the bank, I made free of his phone and tried to find out something about the cones of Runnel. I tried the A.A. first, but drew a blank. Then I tried the Ordnance Survey Office. They refused to make an attempt to trace it. So then I went the round of the map-makers. I was convinced that Runnel was either the name of a place or a man.’

‘Well, did you find out anything or didn’t you?’ I demanded.

‘Not from them,’ he replied. ‘But as a last resort, I rang up the Trinity House people. I thought it might be on the coast. Well, it appears there’s a Runnel Stone lying about a mile off a point called Polostoc Zawn, near Land’s End. It’s a submerged rock and Trinity House keep a buoy on it which gives out a mooing sound.’

‘It’s cones of Runnel,’ I said, ‘not cow of Runnel.’

‘Wait a minute,’ he said, and there was a gleam of excitement in his eyes. ‘Apparently there’s a Board of Trade hut on the point and near this hut are two conical-shaped signs. When they are in line, they give the direction of the Runnel Stone.’

I jumped to my feet in my excitement. Cones of Runnel! It sounded right. Or had Schmidt just chosen those two words at random? I couldn’t believe that. He was bound to give some clues as to the whereabouts of his daughter and the diesel engine he had designed. ‘I think you’ve got it, David,’ I said. ‘Where exactly is this Runnel Stone?’

For an answer he took me over to the desk in the corner where a Ward Lock of West Cornwall lay open, the map of the Land’s End district spread out. ‘There you are,’ he said. ‘Polostoc Zawn, just west of Porthgwarra.’ He flicked over the pages. ‘Here’s what Ward Lock says. “Continuing our walk,” ’ he read, ‘ “we notice on the higher ground on our left two iron cones, one red and the other black and white. They are beacons, which, when in line, give the direction of a submerged rock, known as the Runnel Stone, on which many good ships have met their fate. It is about a mile off the point. On it is a buoy producing a dismal sound like the mooing of a cow.” ’

‘Where’s the nearest station?’ I asked.

‘I don’t think there’s anything nearer than Penzance.’

I nodded. ‘Well, many thanks for your assistance, David. I don’t think I have to remind you of the need for silence.’

‘Here, wait a minute,’ he said. ‘You’re going to Penzance?’ I nodded. ‘You’re not broke by any chance, are you? I mean I don’t expect business is flourishing, but you’re still quite well off, aren’t you?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Yes, I think I am.’

‘Then you can afford to give me a little holiday.’

‘Listen, David,’ I said, ‘this isn’t going to be any holiday. Don’t forget we’re at war. It’s difficult to realise it as yet. But we are, and the chances of coming out of this alive may not be great.’

He looked at me thoughtfully for a moment. ‘You’re serious, are you?’ he said suddenly. Then he laughed. ‘What do you take me for? I want to see this business through just as much as you do.’

I was torn between a desire for his company and a reluctance to endanger anyone else’s life. The excitement aroused in me by the initial process of investigation had given place to a mood of depression. As I saw it, this wasn’t just a single spy or a single criminal I was up against. It was organised espionage. The organised espionage of a power notorious for its efficiency and ruthlessness. That’s the way I looked at it as I stood there in David Shiel’s room on the threshold of what now seems like a nightmare. ‘What is it that attracts you about this business?’ I asked. ‘Is it adventure or Freya Schmidt?’

‘A bit of both, I expect,’ he replied with a grin. ‘I never could resist the idea of beauty in distress.’

‘Well, listen to me,’ I said sharply. ‘There’s no such thing as adventure, except in retrospect. You read stories or hear people talk of adventures. They sound exciting. But the reality is not exciting. There’s pain to the body and torture to mind and nerves, and a wretched death for most adventurers. Few come back to tell their stories to excited audiences. Do you really want to pit your brains and your body, with mine, against something that is probably much too big for either of us? As for Freya Schmidt – well, I must say I thought you’d grown out of the adolescent stage. You’re romancing about a woman you’ve never seen just because she’s in a tough spot.’ My shot got home and I saw him flush. ‘If you ever see her, you’ll probably get a shock. Women with men’s brains usually dress like men and are altogether terrifying.’

‘Have it your own way, old boy,’ he said. ‘But as long as you’ve got my fare, I’m coming with you.’

I saw that his mind was made up, and I must say that I was glad. I sat down and wrote him out a cheque for fifty pounds. ‘There,’ I said, handing it to him, ‘that’s a loan to carry you on. I want you to leave that Calboyd account over till we get back. It’ll be a good excuse for us to go up and see them. Now, I suggest we meet in the lounge at Victoria Station at two o’clock. There’s a Cornish express that leaves Waterloo at three. Try and shake off any followers, but not too obviously. If by any chance one of us is followed to Victoria we’ll still have an hour in which to shake them

off between there and Waterloo.’

‘Good! I’ll be there at two, and no followers.’

CHAPTER FOUR

CONES OF RUNNEL

As soon as we left London we ran into sunshine. It was that bright, rather brittle sunshine that goes with February and an east wind. The sky was a light chilly blue and cloudless, and its colour was reflected in the water, which lay everywhere on the low ground. The fields, as they streamed past, looked sodden, but their green gave promise of a good early bite. As the sun went down, a dull mist spread over the landscape. By the time we ran through Salisbury, with the thin cathedral spire standing like a grey needle out of the gathering gloom, David was dozing in the seat opposite me, his heavy curved pipe lodged in the corner of his mouth. But the rhythmic beat of the wheels had filled me with a wild sense of excitement, and I did not feel like sleep.

Big stations, filled with the noise and bustle of travel, have always thrilled me. A car is a prosaic thing by comparison. Perhaps it is a matter of association. To me, a car is a method of conveying one to the beauties of the country. But a train spells travel. Go to Victoria, Waterloo, Euston – the Continent, the West Country and Scotland come instantly within your grasp. New scenery, adventure, fighting in some remote battle-ground, whatever your soul longs for, the cold ice of the north or the hot sun of the south, is there for the asking if you have money in your pocket. And the incessant clatter of the wheels! It’s the pulse of life, the rhythm of adventure. It’s the urge that makes children want to play trains. It’s the sound that lifts you out of the rut and sets you down in a new world for a week, a month, a lifetime maybe. It brings you to new friends, new loves. It takes you to your death. It takes you to the fear of death. But it is adventure. And listening to the rhythmic beat, the mood of depression that I had felt in David’s studio was gone, and I felt elated.

It was dark long before we reached Exeter, and we passed through Okehampton with the tors of Dartmoor etched black and clear against a full moon. It was past midnight before we glimpsed the sea at Marazion and saw St Michael’s Mount rearing its compact defences out of the silvered waters of the Bay. We went to earth for the night in a comfortable little hotel just opposite Penzance Station. My window looked out across the harbour to the moonlit bay. The outline of a destroyer and the complete absence of lights reminded me that the West Country, as well as London, was at war. I felt the presence of the sea, but everything was very still. I had a hot rum and tumbled into bed. But though I knew I was on the threshold of a big and dangerous task, I slept like a log.

I woke to a dismal sea mist and the mournful cry of a fog horn. ‘The Runnel Stone,’ David murmured, as he took the seat opposite me in the breakfast-room. ‘They may not mean it that way, but it sounds remarkably like a cow.’

‘Well, I hope to God we haven’t been leaping to conclusions,’ I said. The mist had damped my spirits.

‘I’ll be damned surprised if there’s more than one place in this country that could be described as the Cones of Runnel,’ he replied. And I had to admit the truth of that. It was an unusual name. And I fell to wondering what Freya would be like and what sort of trouble lay ahead of us.

This sense of trouble ahead persisted against all the arguments of logic. We had not been followed to Penzance – of that I was certain. We had both been followed on leaving our rooms on the previous day, but had both been able to report on meeting at Victoria that we had shaken our followers off. Even so, we had taken elaborate precautions against any possible hangers-on in getting across to Waterloo. But though I sensed trouble ahead, I was not fighting shy of it. There was merely a slight tautness of the nerves, a tautness which I had not experienced since my climbing days. Of one thing I was glad. I had lived soft during recent years, but I had sat loose in my comfort and the wrench of leaving the rut was not severe.

After breakfast we went in search of a car. David took charge of this expedition. He has a flair in these matters. I remember, at one of his parties, hearing a young fellow, who had been told by David where he could pick up a steam-pressure cooker cheap, say, ‘Anything you want, go and ask old David. He knows so many odd people that he can always tell you exactly where to find anything at a knockdown price.’ But David also had a sense of atmosphere. He turned down a perfectly good Austin, which was offered us at normal hire rates together with unlimited petrol. ‘What!’ he exclaimed, when I protested that all we wanted was a car to get us over about ten miles of country. ‘Turn up in an Austin? My dear Andrew, an Austin is essentially a family car. It’s not the right background for us at all. Besides, you never know.’ Well, he was right about that.

Altogether we wasted about an hour wandering round Penzance, but eventually we ran a big Bentley roadster to earth. We hired it from a back-street garage proprietor and found the owner in dingy lodgings down by the harbour. Neither of us had any doubt about the position. The man was the chauffeur and master was away. David was not scrupulous, however, and when the fellow suggested a pound a day, he said, ‘Ten bob – for yourself.’ The man took the hint, and we left Penzance in style.

The mist had lifted a bit and turned into a downpour, which hit the Bentley in a flurry of wind as soon as we reached open country. We kept to the Land’s End road as far as Lower Hendra, where David turned off to St Buryan. Penzance to Porthgwarra is not more than nine miles, but as soon as we were off the main road, the way became windy and the going slow. Barely two miles short of Land’s End, we turned sharp left into a narrow lane up which the Bentley shouldered its way between reeking hedgerows. We climbed steadily and, breasting a hill by a farm, we suddenly came upon moorland and looked through the driving curtain of rain to the dismal grey of the sea mottled with white-caps.

David slowed the car up as we bore round the shoulder of the hill and took the descent into Porthgwarra. And then simultaneously we cried out and pointed across the valley. Against the rain-drenched background of the hill opposite, the iron cones stood out, sombre and foreboding. They looked like a pair of giant pierrot’s hats, one red and the other a black check, set down carelessly upon the headland. And yet they seemed to have grown out of the ground like dragon’s teeth rather than to have been set down in that desolate spot.

The valley, into which we were descending, ran practically parallel to the coastline, snaking out into the natural inlet of Porthgwarra at the finish. The seaward side of the valley rose steep and bare to the coastguards’ houses and the Board of Trade look-out on the top. Beyond it were the cliffs. They presented an almost solid front stretching to Land’s End. These cliffs are regarded by those who know their Cornwall as the grimmest natural battlements in the country.

As we slid quietly round the bend and into the valley, we lost the wind and the sudden stillness was almost eerie. Porthgwarra had scarcely the right to be called a village. It is just a cluster of cottages huddled together for shelter close by the shore. David drew up at the local shop. We got out and stood for a moment, looking at the heaving mass of water that jostled in the inlet. Behind the regular beat and hiss of the waves on the foreshore we heard the dull roar of the Atlantic out beyond the headland. And behind all this cacophony of sound the mournful groan of the Runnel buoy was borne in on the howling wind.

I led the way into the shop. The sharp note of the bell over the door brought an elderly body from the back parlour. ‘I’m a solicitor,’ I said. ‘I’m looking for a young lady who has recently come to live in these parts.’

‘Ar,’ she said, and looked me over. ‘What would ’er name be?’

I said, ‘Well, that’s the trouble. I’m not quite sure. She used to be a Mrs Freya Williams, but since she divorced her husband I believe she has returned to her maiden name.’ It was a gross libel on the girl, but I could think of no other satisfactory reason for not being able to give her name.

‘Ar, well now, there’s Miss Dassent over to Roskestal.’

‘When did she arrive?’

‘That’ll be two winters ago now.’

&

nbsp; ‘Then that’s not the one,’ I said. ‘The young lady I want to get in touch with must have arrived only a few months back.’

‘Ar, well then, it’ll be Miss Stephens down at the studio you’re wanting mebbe.’ She thought for a moment, and then turned to the back parlour and called out, ‘Joe!’ A grey-haired man with a dark weather-beaten face and a seaman’s jersey emerged. ‘There’s two gentlemen here looking for—’

‘Ar, I heard. It’ll be Miss Stephens arl right that you’ll be looking for,’ he said to me. ‘She came here with ’er boat at the end of the tourist season. She’s got the studio down afore the beach. Might you be a friend of hers?’

‘I have some business to discuss with her,’ I said.

‘Ar, but you’m a lawyer fellow, like?’ I nodded, and he spat accurately into the corner behind the counter. ‘Then it do look as though the Lord ’as sent you. The lass be over in the little cove with two naval men. They want to take her boat, and she’m mighty fond of that boat. You’ll mebbe know the rights of the matter. When I left them five minutes back they were still arguing it out and she were getting mighty sore.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘I’ll go down and see what I can do.’ When we were outside, I said, ‘Looks as though you were right, David, about the Cones of Runnel.’

‘What makes you so sure all of a sudden?’

I laughed. ‘Everything fits so snugly into place,’ I said, as we went down the road to the beach. ‘The tripper season ended about the time that Schmidt got that engine away from Llewellin’s works. And here is this Miss Stephens with a boat. Don’t you see – Swansea is on the coast. What better way of hiding a diesel engine than by putting it into a small yacht.’

David added thoughtfully, ‘The reasoning is sound. But what about this requisitioning party? Don’t tell me that we’ve arrived just in the nick of time to save the heroine from having the secret engine stolen from her by her father’s enemies.’

‘I doubt it,’ I said. ‘You’ve got a thriller mentality, David. But stranger coincidences happen in real life. What is more likely is that we have arrived just in time to see the boat requisitioned by the naval authorities. A lot of these small craft are being called in for patrol work just now.’

High Stand

High Stand The Doomed Oasis

The Doomed Oasis Golden Soak

Golden Soak Levkas Man (Mystery)

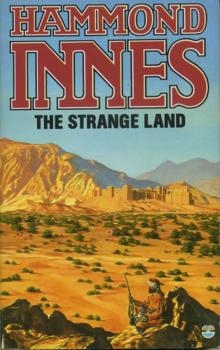

Levkas Man (Mystery) The Strange Land

The Strange Land Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive Attack Alarm

Attack Alarm The Strode Venturer

The Strode Venturer Campbell's Kingdom

Campbell's Kingdom North Star

North Star The Wreck of the Mary Deare

The Wreck of the Mary Deare The Lonely Skier

The Lonely Skier The Black Tide

The Black Tide The Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse Medusa

Medusa Air Bridge

Air Bridge Maddon's Rock

Maddon's Rock The Angry Mountain

The Angry Mountain Wreckers Must Breathe

Wreckers Must Breathe Solomons Seal

Solomons Seal The White South

The White South