- Home

- Hammond Innes

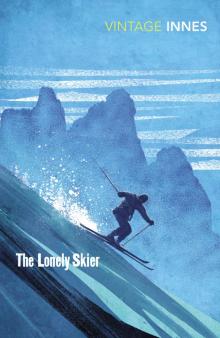

The Lonely Skier Page 3

The Lonely Skier Read online

Page 3

It was dark and the snow was falling when we arrived at Cortina. Once out of the lights of the station our sense of pleasure at having finished the journey was damped by the blanket of steadily falling snow. The soft sound of it was audible in the still night. It hid the lights of the little town and muffled the chained wheels of the hotel bus.

Cortina is like all winter sports’ resorts. It is a veneer of civil-isation’s luxuries planted by hotel-keepers in the heart of a wild country of forests, snow and jagged peaks. Because of the lateness of our arrival, we had arranged to stay the first night at the Splendido and go on up to Col da Varda the next day.

As soon as we passed through the Splendido’s swing doors, the glittering palace lapped its luxury round us like a hot bath. In every room central heating thrust back the cold of the outside world. There were soft lights, dance bands, and the gleam of silver. Italian waiters, with a hundred different drinks, threaded their way through a colourful mob of men and women from a dozen different countries. Everything was laid on—ski instruct-ors, skating instructors, transport to the main runs, ice hockey matches, ski jumping. It was like a department store in which the thrills of the snow country can be bought at so much a yard. And outside the snow fell heavily.

I picked up a pile of brochures on Cortina whilst waiting for dinner. One announced it as ‘the sunny snow paradise in the Dolomites.’ Another became lyrical over the rocky peaks, describing them as ‘pinnacles rising out of the snow and looking like flames mounting into the Blue Sky.’ They spoke with awe of fifty-eight different ski runs and, referring to summer sport at Cortina, stated, ‘it is almost impossible to be tired at Cortina: Ride before breakfast, golf before lunch, tennis in the afternoon and a quick bath before dressing for dinner—still one is ready to dance until the early hours.’ Nothing out of the ordinary could happen here, I felt. They had made a playground of the cold snow, and the grim Dolomite bastions were pretty peaks to be admired at sunset with a dry Martini.

Joe Wesson had something of the same reaction. He suddenly materialised at my elbow. He wore rubber-soled shoes and moved quietly for such a large man. ‘Not a hair out of place, eh?’ he said, looking at the brochure over my shoulder. ‘It’s like the Italians to try to tame Nature with a pot of brilliantine. But it can’t be far from here that twenty thousand men died trying to get Hannibal’s elephants through the passes. And only a year or two back, I suppose, a lot of our blokes were frozen to death attempting to get through from Germany.’

I tossed the brochures back on to the pile. ‘It might be Palm Beach, or the Lido, Venice, or Mayfair,’ I agreed. ‘Same people—same atmosphere. Only I suppose it’s all white outside.’

He gave a snort of disgust and led the way into dinner.

‘You’ll be glad enough to return to it,’ he muttered, ‘after you’ve had a day or two up in that damned hut.’

As I sat down, I glanced round the room at the other diners, wondering whether the girl who had signed herself ‘Carla’ in that photograph would be there. She wasn’t, of course, though the majority of the women in the room were Italian. I wondered why Engles should expect her to be at Cortina.

‘No need to try and catch their eyes,’ Joe Wesson said through a mouthful of ravioli. ‘Judging by the looks of most of ’em, you’ve only got to leave your bedroom door open.’

‘You’re being unnecessarily coarse,’ I said.

His little bloodshot eyes twinkled at me. ‘Sorry, old man. Forgot you’d been in Italy long enough to know your way around. Is it a contessa or a marchesa you’re expecting?’

‘I don’t quite know,’ I replied. ‘It could just as well be a signora, or even a signorina, or just a common or garden little tart.’

‘Well, if it’s the last you’re wanting,’ he said, ‘you shouldn’t have much difficulty in this assembly.’

After dinner I went in search of the owner of the hotel. I wanted to find out what local information I could about Col da Varda and its slittovia. Our accommodation at the chalet had been booked through him and I thought, therefore, that he should be able to tell me what there was to know.

Edouardo Mancini was a short stocky man of very light colouring for an Italian. He was part Venetian and part Florentine and he had lived a long time in England. In fact, he had once been in the English bob-sleigh team. He had been among the great of the bob-sleigh world. But he had had to pack it up ten years ago after a really bad smash. His right arm had been broken in so many places that it was virtually useless.

Once he had doubtless been a slim, athletic figure, but when I met him he had put on weight so that his movements were slow. He was a heavy drinker. I imagine that started after his final accident. It was not difficult to pick him out among his guests. He looked almost a cripple, his big body moving slowly, almost stiffly among them. He had broken practically every bone in his body at one time or another and I believe he carried quite a weight of platinum around in place of missing bone. But in spite of this, his rather dissipated features were genial under his mop of titian hair, which rose almost straight up from his scalp, giving him height and a curiously youthful air. He was a very wealthy man and the biggest hotelier in Cortina.

Most of this I learned from an American I had met in the bar before dinner. He had been a Colonel in the American Army and had had something to do with Cortina when it was being run as an Allied leave centre.

I found Edouardo Mancini in the bar. He and his wife were having a drink with my American friend and two British officers up from Padua. The American introduced me. I mentioned that I was going up to Col da Varda the next day. ‘Ah, yes,’ Mancini said. ‘There are two of you—no? And you are planning to do a film? You see, I know who my guests are.’ And he beamed delightedly. He spoke English very fast and with just the trace of a Cockney accent mixed up with the Italian intonation. But it was very difficult to follow him, for his speech was obstructed by saliva which crept into the corners of his mouth as he talked. I imagine his jaw had been smashed up in one of his accidents and had not set properly.

‘Col da Varda belongs to the hotel, does it?’ I asked.

‘No, no—good heavens, no!’ He shook his large head vehemently. ‘You must not have that idea. I would not like you to blame all the short-comings of the place on me. You would obtain a bad impression. My hotel is my home. I do not have anybody here, you understand. You are my guests. That is the way I like to think of all these people.’ And he waved his hand towards the colourful crowd that thronged the bar and lounge. ‘If anything is wrong, we look at it as you would say, my wife and I, we are bad hosts. That is why I will not have you accuse me of Col da Varda. It is not comfortable there. That Aldo is a fool. He does not know how to arrange people. He is lazy and, most terrible of all, he is no good for the bar. Is that not so, Mimosa?’

His wife nodded and smiled from behind her Martini. She was small and attractive and had a nice smile.

‘I will—how you say it?—sack him. Please excuse my English. It is many years since I was in England. I had hotels in Brighton and London. But that was long before the war.’

I assured him that he spoke excellent English. Indeed, if I had spoken Italian as well in my own country I should not have felt impelled to apologise.

He nodded, as though that were the reply he expected. ‘Yes, I will give him the sack.’ He turned to his wife. ‘We will give him the sack, dear, the day after tomorrow and we will put Alfredo there. He has a good wife and they will run it well.’ He put his hand on my arm. ‘In the meantime, you will not blame me—yes? I am only what your doctors would call in locum parentis at the moment. I do the bookings. But on Friday it will become a little piece of the Splendido. Then, if you stay long, you will remark a difference. But it will take time, you understand?’

‘You mean you are taking it over?’ I asked.

He nodded. ‘On Friday. There is an auction. I shall buy it. It is all arranged. Then you will see.’

‘I don’t quite get you, Mancini,�

�� said the American. ‘Don’t you have to bid at an Italian auction? A thing like that, auctioned in America, would attract all sorts of real-estators and business men who’d enjoy running a toy like a slittovia. I know you’re the biggest hotelier in the place. But I guess there are others who might like that little property.’

‘You do not understand,’ Mancini said with a quick crinkling of the eyes. ‘We are not fools here. We are business men. And we are not like the cats and dogs. We arrange things with orderliness. The others do not want it. It is too far out for them. But I have a very big hotel here and I am always progressive. It will make money because Col da Varda will become the Splendido’s own ski run. I shall run a bus service and it will not be crowded like the Pocol, Tofana and Faloria runs. So, no one will bid but me. An outsider would never buy. He knows there would be a boycott.’

‘I’d like to see an Italian auction,’ I said. ‘Where is it being held?’

‘In the lounge of the Luna. You really wish to come?’

‘Yes,’ I told him. ‘It would be very interesting.’

‘Then you shall come with me—yes?’ Mancini shook his head, smiling. ‘But it will be very dull, you know. No fireworks. There will be just the one bid—a very low one. And then it will be over. But if you really wish to come, meet me here at a quarter to eleven on Friday and we will go together. After, we will have a little drink to celebrate—also because, if I do not give you a drink, then you will feel the time is wasted.’ He gave a deep throaty chuckle. ‘The Government will make little out of it. Which is good because we do not like the Government here. It is of the south and we have a preference for Austria, you know. We are Italian, but we found the Austrians governed better. If there were a plebiscite, I think this part of the country would vote to return to Austria.’

‘What’s the Government got to do with it?’ asked the American. ‘As I remember it, the slittovia was constructed by the Germans for their Alpine troops. Then a British division took it over. Did the British Military sell out to the Italian Government?’

‘No, no. When the war was nearly over, the Germans sold it cheap to the man who once owned the Excelsiore. It was from him that the slittovia was requisitioned by the British. His hotel was requisitioned, too. But when the British left, he found it difficult. He had been too great a collaborator. We persuaded him that it would be best to sell and a small syndicate of us bought him out. You see, we are quite a little family here in Cortina. If things are not right, we make adjustments. That was a year ago. Business was not good, you know. We did not want the slittovia then. It was sold very cheap to a man named Sordini.’ He made a dramatic pause. ‘That was a strange business—eh? We did not know. How could we? He was a stranger. It was a big surprise to us when he was arrested. And the two workmen he had up there—they were Germans, too.’

‘I don’t understand,’ I said, trying to hide my excitement. ‘Was this Sordini a German?’

‘But yes,’ he said in a tone of surprise. ‘The name Sordini was an alias. He took it in order to escape just retribution for all his crimes. It was all in the papers. It was even on your own radio—I heard it myself. It was a captain of the carabinieri who arrested him. The captain and I were drinking together here in this bar the night before he went up to the hut. We think Sordini must have bought the place as a hideout. They took him to Rome and put him in the Regina Coeli. But he did not kill himself in that prison. Oh no—probably he had friends and hoped to escape, like Roatta, Mussolini’s commander in Albania, who was reported to have strolled out of the prison hospital in his pyjamas and got away down the Tiber in a miniature submarine. No, it was when he was handed over to the British to join the rest of the war criminals that he took the poison.’

‘What was his real name?’ My voice sounded unnatural as I tried to show only a casual interest.

‘Why—Heinrich Stelben,’ he answered. ‘If you are interested you shall see the cuttings from the newspapers. I keep them because so many of my guests are interested in our local celebrity.’ The barman produced them immediately.

‘May I borrow these?’ I asked.

‘But certainly. Only return them please. I wish to have them framed.’

I thanked him, confirmed our arrangement for going to the auction and hurried away to my room. I was greatly excited. Heinrich Stelben! Heinrich! I switched on the table light and took out the photograph Engles had given me. ‘Für Heinrich, mein liebling—Carla.’ It was a common enough name. And yet it was strange. I picked up the cuttings. There were two of them and they both were from the Corriere della Venezia. They were quite short. Here they are in full, just as I translated them that first night in Cortina:

Translated from the Corriere della Venezia of November 20, 1946.

CARABINIERI CAPTAIN CAPTURES GERMAN WAR CRIMINAL IN HIDING NEAR CORTINA

Heinrich Stelben, German War Criminal, was captured yesterday by Capitano Ferdinando Salvezza of the Carabinieri in his hideout, the rifugio Col da Varda, near Cortina. He was known in the district as Paulo Sordini. The Col da Varda rifugio and slittovia were bought by him from the collaborator, Alberto Oppo, one-time owner of the Albergo Excelsiore in Cortina.

Heinrich Stelben was wanted for the murder of ten British Commandos in the La Spezia area in 1944. He was an officer of the hated Gestapo and he is also accused of assisting in the deportation of Italians to Germany for forced labour and of the murder of a number of Italian political prisoners of the Left. He was also responsible for transporting several consignments of gold from Italy to Germany. The largest consignment was from the Banco Commerciale del Popolo of Venice. Half of this consignment mysteriously disappeared before it reached Germany. Stelben states that his troops mutinied and seized part of the gold.

This is the second time that Heinrich Stelben has been arrested by the Carabinieri. The first occasion was at a villa on Lake Como shortly after the surrender of the German Armies in Italy. He was taken to Milan and handed over to the British for interrogation. A few days later he escaped. He disappeared completely. Carla Rometta, a beautiful cabaret dancer, with whom he had been associating, also disappeared.

It is understood that his latest arrest was the result of information lodged with the Carabinieri. With him, at the time of his arrest, were two Germans posing as Italian workmen. It is not known yet whether they are also war criminals.

Heinrich Stelben and his associates have been removed to Rome where they have been lodged in the Regina Coeli.

Translated from the Corriere della Venezia of November 24, 1946.

GERMAN WAR CRIMINAL COMMITS SUICIDE

Shortly after Heinrich Stelben, infamous German War Criminal, had been taken from the Regina Coeli and handed over to British Military Authorities, he committed suicide, according to a British press message. Whilst being interrogated, he broke a phial of prussic acid between his teeth.

The two Germans who had been arrested with him near Cortina were involved in the recent rioting in the Regina Coeli. It is understood that they were killed in the course of an attack on the Carabinieri by the inmates of the central block. It is not known whether they were wanted as war criminals.

I read those two cuttings through. And then I glanced again at the photograph. Carla! Carla Rometta! Heinrich Stelben! It was certainly a strange coincidence.

2

A ‘Slittovia’ is Auctioned

JOE WESSON LOOKED tired and cross when I met him at breakfast the next morning. He had been up until the early hours playing stud poker with two Americans and a Czech. ‘I’d like to get Engles out here,’ he rumbled morosely. ‘I’d like to put him on top of that damned col, cut the cable of the slittovia and leave him there. I’d like to give him such a bellyful of snow that he’d never even face ice in a drink again.’

‘Don’t forget he’s a first-class ski-er,’ I said, laughing. Engles had been in the British Olympic team at one time. ‘He probably likes snow.’

‘I know, I know. But that was in his early twenties, befo

re the war. He’s got soft since then. That’s what the Army does for people. All he wants now is comfort—and liquor. You think he’d enjoy it up there in that hut—no women, no proper heating, nobody around to tell him how marvellous his ideas are—probably not even a bath?’

‘Anyway, there’s a bar,’ I told him.

He gave a snort. ‘Bar! I’m told that the man who runs that bar can trace congenital idiocy back through his family for three generations, that he specialises in grappa made from pure methylated spirits and, furthermore, that he is the dirtiest, laziest, stupidest Italian any one has ever met—and that’s saying something. And here I’m supposed to drag my camera up to the top of that God-damned col and prance about in the snow taking pictures to satisfy Engles’ megalomania. And I don’t feel like going up a slittovia this morning. Those sort of things make me dizzy. It was constructed by the Germans and the man who owned it was arrested only a fortnight ago as a German war criminal. The cable is probably booby-trapped.’

High Stand

High Stand The Doomed Oasis

The Doomed Oasis Golden Soak

Golden Soak Levkas Man (Mystery)

Levkas Man (Mystery) The Strange Land

The Strange Land Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive Attack Alarm

Attack Alarm The Strode Venturer

The Strode Venturer Campbell's Kingdom

Campbell's Kingdom North Star

North Star The Wreck of the Mary Deare

The Wreck of the Mary Deare The Lonely Skier

The Lonely Skier The Black Tide

The Black Tide The Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse Medusa

Medusa Air Bridge

Air Bridge Maddon's Rock

Maddon's Rock The Angry Mountain

The Angry Mountain Wreckers Must Breathe

Wreckers Must Breathe Solomons Seal

Solomons Seal The White South

The White South